Dispatches from an Autistic English Teacher

Career failure, neurodivergent revelation, and (at the bottom of the post) a reading of "Sailing to Byzantium" by W.B. Yeats

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress

It took me twenty-four years to understand that there was no shame in leaving student teaching halfway through my senior year of college.

In 1999, I was a Secondary English Ed major at the University of Georgia. I’d spent my first three years of college alternately declaring and changing degree programs: Social Work. Child Development. Early Childhood Education. The only thing I knew about my inscrutable self was that nothing suited. Nothing that grabbed my heart, like literature, led to a path that tapped into my talents, which were pretty much—reading and writing about literature.

My talents did not include talking about literature because—you guessed it—I was undiagnosed autistic, selectively mute and socially confused. Put me in front of a room of desks, and the sea of student faces gazing back at me turned my thoughts to mush. Why were we talking about Wordsworth and the British Romantics? What was the purpose of this Mozart music-and-journaling exercise again? I went blank. I couldn’t do this thing called classroom teaching. I couldn’t do it organizationally in my brain. I couldn’t do it socially with the students.

The high school to which I was assigned was a thirty-minute drive into the county from my college town. I wept all the way there every morning in the early dawn dark. I entered the glass double doors and walked the hallway to my mentor teacher’s classroom, my stomach an increasingly knotted alarm: something was wrong.

When I told my professors I’d changed my mind—that I’d made a mistake—they were surprised. “You weren’t the one we expected to drop!” Something about me had inspired their confidence, but I didn’t know what. For my last semester of undergrad, I returned to the UGA’s Park Hall, ascending its old stone stairs to attend the three English classes the Education department agreed could complete my degree, which would be a Bachelor’s of Science in Education, sans certification.

What did I know back then of overstimulation, of the need for sensory breaks, of the way reducing eye contact can enable better brain function? All I knew was that I couldn’t do this work, that I was falling apart, that I had failed. That teaching was the wrong profession for me.

One of the three English classes I enrolled in that final spring semester was a survey of Irish Literature. I still remember, clear as day, the assignment to memorize, recite, and spend fifteen minutes talking about one of W.B. Yeats’s earthy, strange, spiritual poems. You already know what I chose: “Sailing to Byzantium.” And this is what happened.

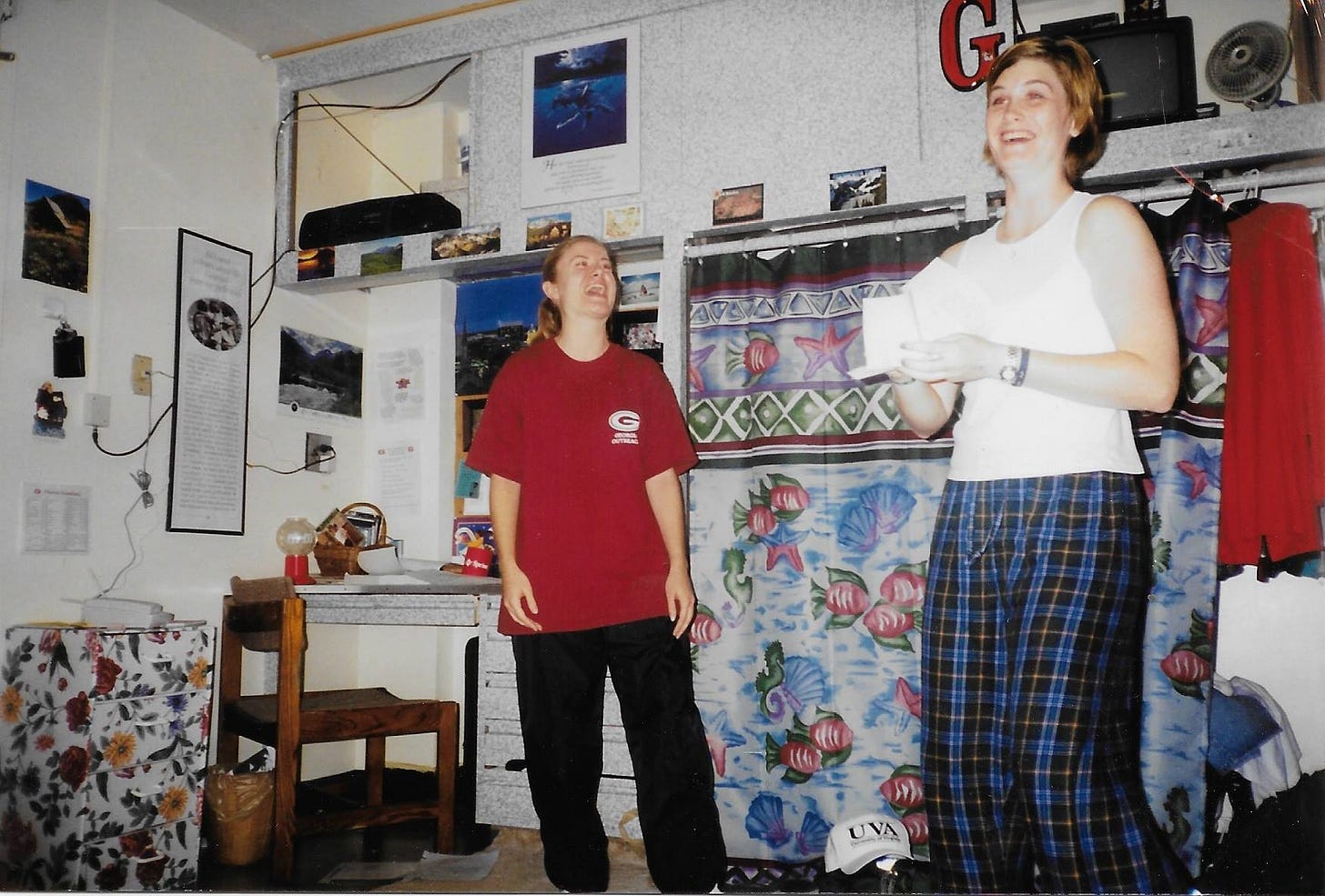

First, I memorized that poem. I memorized the hell out of it. I could recite it in my sleep to this day. I did the work of memorizing it—I see this now—in community. My roommate created an exuberant interpretive sequence to help me remember the lines. (You can imagine her motions: “the young in one another’s arms”; “whatever is begotten, born, and dies.”) Then we took our show on the road—or into the dorm hallway, as it were. We performed for friends, and my God, we had fun. And then.

And then. I went to class and did my thing, which was to recite the poem (interpretive roommate not present) and then talk about the poem, which I did. I held a printed page marked up with underlines and notes, and Lord, I enjoyed it. And then I finished and I looked at the teacher—an aged British fellow with wild grey hair and a grizzled beard—and his eyes were alight and the next words out of his mouth were to the entire class: “We’ll see everyone next time.” Because I had talked for the entire fifty minute class period.

Because I had taught the class.

Do you know when I realized I had taught the class? That I had—hear me, self—done a good, one might even say successful, job teaching in that moment? This year.

But I look back now, and I see a shimmering self just waiting to for the right time to become her whole self, and then give that self to others—in the classroom.

It was only three years ago that I learned what kind of teacher I could be, and it almost didn’t happen. The first semester of my return to teaching in a Tenth Grade English classroom went sideways. I went sideways: socially overwhelmed, mentally confused, physically burned out. But halfway through the year, I had a revelation that changed everything.

I learned that I am autistic.

Then I learned more. I learned that if I reduce direct eye contact with the students, I can understand better what they say. I learned that if I let myself stim a little (swivel teacher chairs for the win; bursting out in song mid-lecture for the extra extra win), my body gets less stressed. I learned that when I lean into who I actually am—this particular constellation of strengths and weaknesses, talents and needs known as Mrs. Martin—the students themselves have a better experience. They relax, they lean in, they learn, they grow.

Don’t miss what I just said: when I am free to be myself, those I serve are free to become themselves, too.

I didn’t do anything wrong by quitting teaching back in my senior year. I did what I needed to do to take care of myself. I did the only thing I could do, not yet understanding myself. I felt shame at the time. I felt shame for all the years in my twenties and thirties when I couldn’t find a career that would hold. But I look back now, and I see a shimmering self just waiting to for the right time to become her whole self, and then give that self to others—in the classroom.

It isn’t just Yeats’s aged man that is a paltry thing, but any of us who can’t see ourselves yet. Scratch that. None of us are paltry things, ever. But failure and shame make us feel paltry until, until. Until “Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing / For every tatter in its mortal dress.”

This is my fourth year back in a classroom as a forty-something-year-old woman. I’ve got some tatters in my mortal dress. But watch me. Watch me clap my hands and everlovingly stimmingly autistically sing, and louder sing, and bring any student along who also needs the chance to become themselves.

I call this Singing School.

You're using Yeats' poem to tell your story, and it's so beautiful.

Beautiful. I guess there are people out there who can teach without bringing their authentic selves to the classroom? I've never been able to do it myself and not interested in trying. Also, thinking I might burst into song sometimes now myself!